The Surprising Comparison

An ant colony finds the shortest route to food in a similar way the human brain learns to play the piano. That sounds bizarre. But it's true.

How Ant Colonies Work

Ants live in colonies of thousands—sometimes millions—working together. Each ant has a job, but no single ant is in charge. There's no boss giving orders. No ant knows the whole picture. Yet the colony solves problems together. Picture this. A scout ant finds a biscuit crumb fifty metres from the nest. It heads back home, leaving a chemical trail behind it. Other ants pick up the scent and follow. But some ants wander off the path. Maybe one stumbles onto a shortcut. Within a day, every ant uses the shorter route. Nobody drew a map. No leader made the decision. Yet somehow the colony figured it out.

The Chemical Trail System

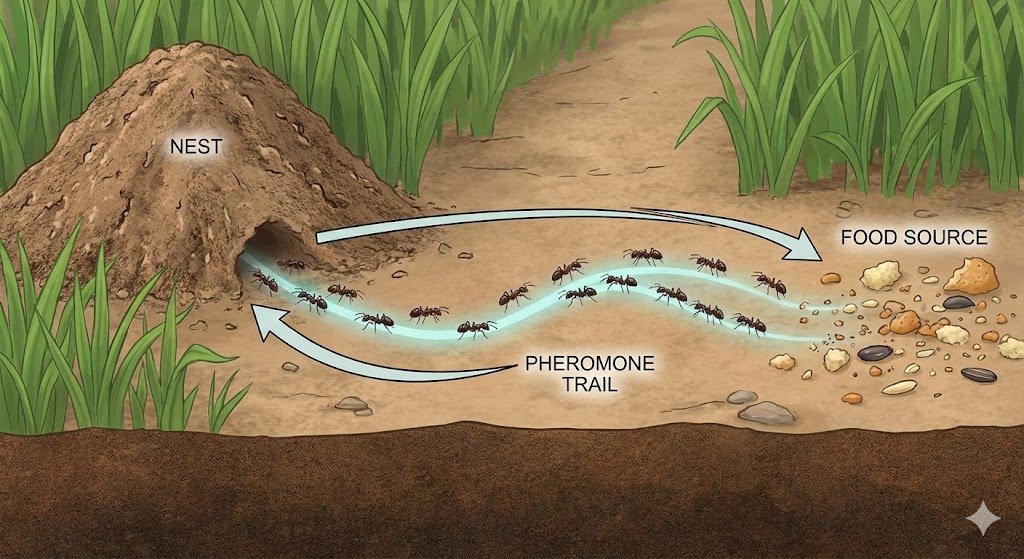

Here's how it works. Every ant leaves behind a chemical called a pheromone as it walks. This chemical slowly evaporates. Where the smell is strong, ants tend to follow. Where it's weak, they wander randomly.

Why Shorter Routes Always Win

Now imagine two paths to that biscuit crumb. Path A winds around a rock—sixty metres. Path B goes more directly—fifty metres. Both paths get ant traffic. Both get pheromone trails. But Path B gets more traffic because ants finish the journey faster. They get back to the nest sooner. They make more trips. More trips means more pheromone gets laid down. Simple maths: shorter routes build stronger smells faster.

As Path B gets smellier, more ants follow it. More ants means more pheromone. More pheromone attracts more ants. Meanwhile, Path A gets less traffic. Its smell fades. Eventually nobody uses it. Three simple rules created this: leave a smell trail, follow strong smells, let the smell fade over time. No individual ant worked out which route was better. The system just... worked.

The Brain Works the Same Way

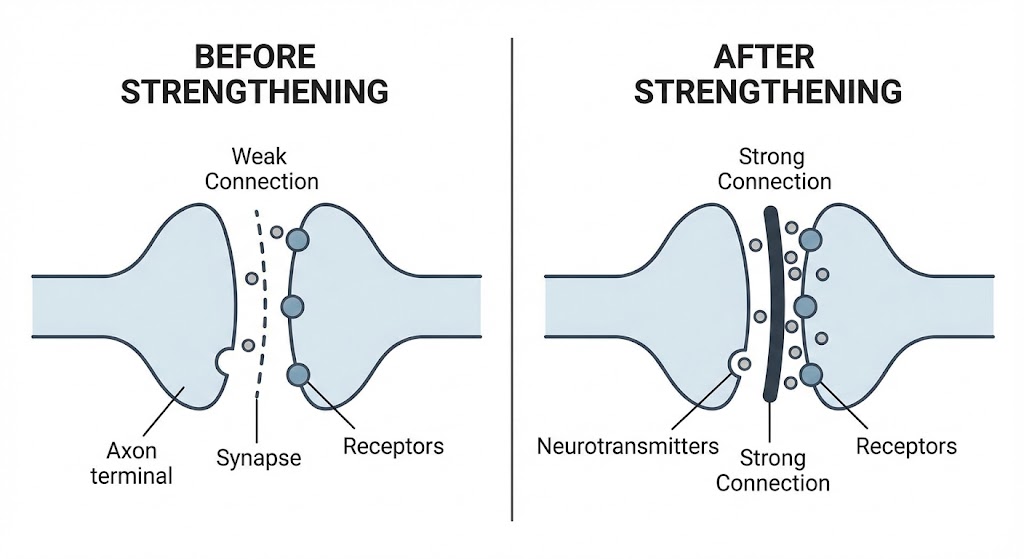

The human brain contains roughly 86,000,000,000 nerve cells packed into about one and a half kilograms of tissue. Despite all that complexity, it uses exactly the same trick as an ant colony. Brain cells—neurons—send signals across tiny gaps called synapses. When the same pathway gets used repeatedly, that connection gets stronger. Use it rarely? It weakens. A psychologist called Donald Hebb figured this out in 1949. He said neurons that fire together, wire together. The brain strengthens the routes it uses and lets the rest fade away. Just like the ant colony.

Learning Any Skill

Learning any skill works this way—swimming, riding a bicycle, playing a musical instrument. Take someone learning piano. At first, their fingers fumble. They try different movements. Some work, some don't. The ones that work—hitting the right notes at the right time—get repeated. The brain pathways behind those movements get stronger. The fumbles don't get repeated. Those pathways weaken. After a few weeks, their fingers know where to go. Not because they consciously memorised every movement. Because repetition strengthened the right pathways and weakened the wrong ones. The brain found shortcuts without anyone planning it.

This Pattern Appears Everywhere

This pattern appears everywhere once someone knows what to look for. Those dirt paths worn across grass where people decided the paved path took too long? Those are called desire paths. Every person walking across that grass presses down the vegetation a bit. The more people who walk the same way, the clearer the path becomes. Rarely used routes stay overgrown and difficult. Eventually everyone uses the shortest route. Nobody planned it. People just walked, and the path emerged.

The internet uses the same trick. Routers track which paths send data packets quickly. Popular routes get prioritised. Slow routes get downgraded. Some systems even send out test packets that mark successful routes, with the marks fading unless other packets reinforce them. Sound familiar? The whole internet finds its best routes using ant colony logic.

What Makes This Work

What makes this work is that nothing needs the whole picture. Individual ants don't understand geometry. Individual neurons don't know what skill is being learned. Individual routers don't know the entire internet. Each one follows simple local rules. The clever bit emerges from how they interact. And when things change—a stick blocks the ant path, part of a brain gets damaged, a server goes down—the system adjusts itself. New routes get explored. Good patterns get reinforced. Bad patterns fade.

The Downsides

There are downsides. Ant colonies can get stuck on a bad route if things change too fast for the pheromone to clear. Brain pathways, once they're really strong, resist change. Someone trying to fix a bad habit in their piano playing after months of wrong practice faces a problem. Those neural pathways are so reinforced that they need to be deliberately broken down before building new ones. Much harder than learning it right the first time.

What It All Means

But the basic trick remains brilliant. Complex problems—finding the best route, learning a skill, routing internet traffic—get solved by simple parts following simple rules. Nothing needs to understand the whole system. Smart behaviour emerges from simple interactions, not from planning.

That scout ant had no idea which route was best. The ants who eventually walked the shorter path weren't trying to be efficient. The colony solved the problem through chemical trails and evaporation. The brain does the same. Billions of neurons finding shortcuts by strengthening what works and letting the rest fade. Pedestrians do it too, wearing paths across parks that reveal routes the architects never thought of.

Different systems. Same trick. Smart outcomes without anyone being smart. Just simple rules, repeated actions, and things that fade away.

Topics: #neuroscience #learning #antcolonies #brainplasticity #distributedintelligence #neuralpathways #skillacquisition #hebbianthinking #ArchitectureOfIntelligence

Further Reading

These links dig deeper into the topics covered here:

Ant Colonies:

- Ant Colony Optimization - Wikipedia - Lots more reading on the world of the ant

- Swarm Intelligence Algorithms - DataCamp - Clear guide showing how ant colony ideas get used in computing

Brain Learning:

- Neural Plasticity of Development and Learning - PMC - Academic paper on how brains adapt through experience

- Neuroplasticity for Educators - n2y - Practical guide to how brains change and develop

How This Essay Reflects YFL Values

This essay presents research-backed information about how simple rules create intelligent outcomes—from ant colonies to brain learning—without telling readers what to do with it. Multiple examples show what works whilst acknowledging limitations, trusting readers to draw their own conclusions about how these patterns might apply to their own understanding of learning and change.

This HWTK essay is an adapted extract from the academic YFL essay The Architecture of Intelligence: From Termite Colonies to Human Brains, which provides a deeper exploration of distributed intelligence across biological and technological systems.

Copyright Notice

© 2025 Steve Young and YoungFamilyLife Ltd. All rights reserved.

"Hey!, Want To Know" is a copyrighted content format of YoungFamilyLife Ltd.

This essay was developed collaboratively using AI assistance to research academic sources and refine content structure, while maintaining the author's original voice, insights, and "Information Without Instruction" philosophy. No part of this essay may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the copyright holders, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law.

For permission requests, contact: info@youngfamilylife.com